This post is at least a year old.

The health and stability of the open-source ecosystem is back in the ~discourse~, in no small part thanks to the ongoing nightmare with Log4j2 and CVE-2021-44228.

This post is my own contribution to that discourse, aimed at delivering a

swift kick in the ass to anyone who thinks that we’re currently doing a good

job of either (1) tracking and managing the tangled web of dependencies we’ve woven, or

(2) supporting the maintainers whose un{,der}paid we all transitively depend on.

See also: Weird architectures weren’t supported to begin with.

Most programmers are familiar with the bus factor in software engineering: the number of engineers on a project who would need to have disaster befall them (being “hit by a bus”) in order to completely stop meaningful development.

For many open source projects, the bus factor is 1: a single maintainer performs the overwhelming majority of active development and support work, and controls the various credentials that distribute the project to the larger ecosystem1.

Even when projects develop formal governance (either independently, or via an umbrella group like the ASF) and collect multiple maintainers, the bus factor remains low: many people might hold commit or management permissions, but only a handful posses the overarching technical knowledge to make major changes or urgent, high-pressure fixes without doing more harm than good. Governance itself cannot solve this problem, because there’s only one thing that can: paying more open-source engineers enough to become experts on the systems they’re tasked with maintaining.

But these are staid observations, comprehensively argued by better engineers than me. So I’m going to focus on a related, but different metric: the blast radius for open source maintainers and their projects.

Open source projects exist on a spectrum of success2:

…and so forth, with everything in between.

The success of an open source project is only loosely tied to conventional engineering metrics: more engineers do necessarily not make a more popular project, nor does the “quality” or experience of those engineers guarantee success. Many projects (rightfully!) start as amateur experiments, and are picked up in good faith by the larger community because they solve real problems.

And so, we end up where we are today: we all depend on extraordinary amounts of open-source software, the quality (in terms of bugs, vulnerabilities, &c) of which is not strongly tied to how much we depend on it.

This is where I’d like to make my own ~infosec thoughtleader~6 contribution to the discourse: the concept of a blast radius for open source projects and their maintainers:

A project’s blast radius is the amount of value7 that the world’s companies and maintainers will need to expend if a critical vulnerability is discovered in the project.

A maintainer’s blast radius is the sum of the blast radii for all of the projects they maintain that meet both of the following conditions:

Open source blast radii have second-and-higher-order costs: they take time and money away from everyday engineering priorities (or even stop work altogether), require developers to rotate credentials and re-image their machines, and incentivize all kinds of well-intentioned but mostly useless corporate reactions10.

Using the definition above, I’m going to carve out a few conditions for my own projects:

I will not count open-source projects that my company holds the copyright to, unless I am the de facto sole maintainer and they are de facto unmaintained in the absence of supporting contracts.

I will not count projects that are widely used, but have effectively zero recurring maintenance overhead. Projects in this group include collections of shell scripts with minimal dependencies, or projects that are so stable that my only ongoing maintenance effort is reviewing automated dependency updates.

In my capacity as Homebrew’s least prolific and laziest maintainer, I maintain ruby-macho, the Ruby library that Homebrew uses to parse and rewrite every binary (executable, shared object, &c) that gets installed on macOS hosts. I’m proud of the work I did to develop ruby-macho, particularly because it requires so little maintenance: apart from dependency updates, it’s only needed 1-2 small changes a year to keep abreast with Apple’s changes to the Mach-O format.

At some point, the maintainers of CocoaPods (also written in Ruby) also needed Mach-O parsing, and adopted ruby-macho for their own purposes. By their metrics, CocoaPods is used to manage the dependencies in three million applications.

That brings us to:

A couple of million Homebrew users11, most of whom are developers, performing around 36 million package installs a month12.

Three million macOS, iOS, tvOS, and watchOS applications that use CocoaPods to manage their dependencies, trickling down to who-knows-how-many-millions-or-billions13 of desktop and mobile users.

A remotely exploitable vulnerability in ruby-macho would be a disaster: just about every engineer who develops on macOS would need to uninstall or at least avoid invoking Homebrew until a patch is available. Large parts of the Apple application ecosystem would need to be audited for incursion.

I helped write winchecksec as a side product of a funded research program at work. Like ruby-macho, it needs a relatively light touch: small updates whenever Microsoft adds another mitigation or relevant security metadata to the PE format, but nothing else.

At some point, $LARGE_ENTITY added winchecksec to the CI for

$LARGE_PROGRAM14. I didn’t ask them to do that, but

they did, and it’s still there for all I know. And that’s good! It’s a good tool, another

one that I’m proud of. But once again my blast radius has grown: an exploit against winchecksec

would potentially mean having to deliver client patches to hundreds of millions of users across

every mainstream operating system. Not an enviable task.

I excluded from consideration some of the largest projects I’ve worked on recently, primarily because their bus factors are thankfully higher than 1 (in some cases, much higher).

But that alone doesn’t mean that those projects are adequately funded or healthy along any particular metric15, or even that those projects don’t have large blast radii. It only demonstrates that my own blast radius smaller than the sum of the radii of all the projects I help maintain, a fact that I’m eternally thankful for.

This points to a useful metric to optimize for: some projects will always have large blast radii16 but, in an ideal world, every maintainer would have a personal blast radius of 0.

Right now, all is calm: to the best of my knowledge, nobody is trying to turn my open source work into a liability for the projects and engineers who depend on it. But that doesn’t change the threat.

What can I (or anyone else) do to improve the situation? I can think of a handful of things:

Ludicrous amounts of documentation. I’m one of those people who thinks that nearly every code surface should be documented, not just with structured machine-parseable specifications but also with the mental state of the engineer who wrote it. Mental states give future maintainers (including the ones who might be fixing my vulnerabilities!) insight into the why and not just the what of the code they’re grappling with.

Continuity via automation. I try to have most of my projects perform their core versioning, packaging, &c tasks via CI: new maintainers do not need access to my local machine or private credentials to perform a new release.

This has some serious potential downsides, but they also mean that my projects probably won’t become ghost ships: bustling with users and contributors, but unable to release under their “canonical” name because of missing credentials.

Bringing more people on. There’s nothing magic or special about the code I’ve written: anybody who knows the language(s) that the projects are written in should be able to contribute meaningfully (and historically have!).

The trick is getting those people to become maintainers qua the bus factor, which presents two problems: it demands a time commitment from people who have no obligations towards me, and involves trust. The latter is the perennial problem in open source and supply chains, one to which there is no good general solution. But moving projects into foundations and umbrella organizations appears to be a general improvement: organizations can vet new maintainers and provide a final safety net in the event of malicious maintainers or outright disappearance.

With each of these steps, the blast radius of each project gets a little bit smaller: even

in the event of my total vaporization by a sufficiently high-speed bus disappearance, another

maintainer could step in, get a feel for the territory using my notes, and release a version

with a fix in a timely manner. The vulnerability might still happen, but we can cut back the

time on the fix and save everyone a whole bunch of time and money in the process.

I’ve tried my best to do some of these. But it should come as no surprise that some (all?) of them take time17, and you know what they say about time.

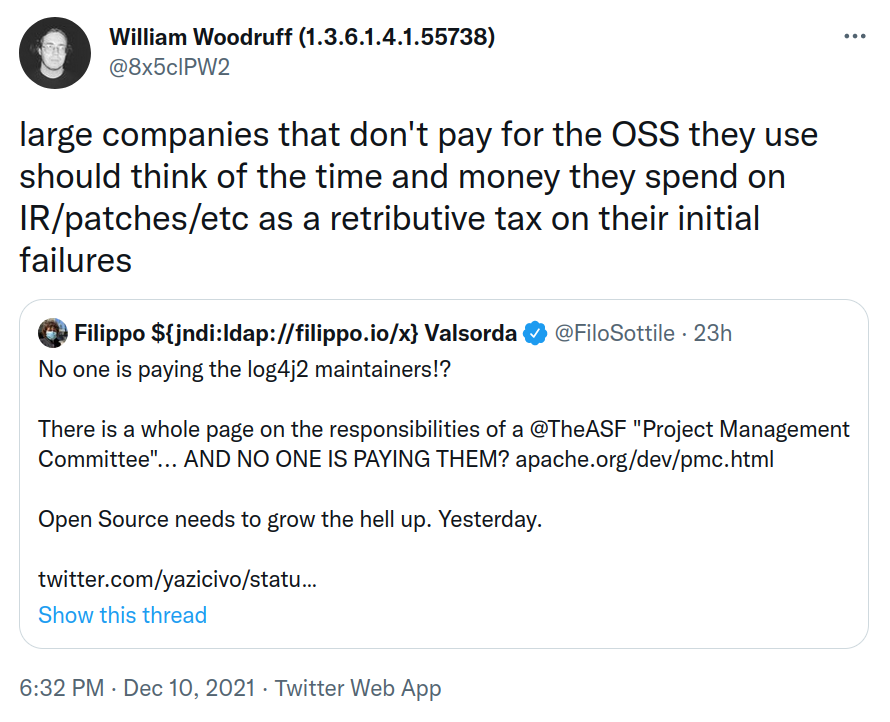

I beat myself to the punch a little bit on the Blue Bird Site:

We are not going to make meaningful progress on open-source sustainability until companies start running the books and tallying up the money they’re losing by failing to pay for the open-source labor they rely on.

Many current corporate incentives run counter to a positive change here: companies see their incident response and blue teams as a fixed, sunk cost that they might as well get some value out of when the shit hits the fan18. What they don’t seem to see is the knock-on effects mentioned above: the hours-turned-days-turned weeks lost each time a work-stopping exploit happens, to say nothing of the avalanche of policy and procedural changes that follow every incident.

I’m under no delusion I am a particularly important player in the open source world, or that the projects I’ve listed above deserve special attention19. The point is in fact the opposite: I am a relative nobody, and my work still ends up on the critical path for millions of people. And that’s business as usual!

This post ended up being more of a ramble than I was hoping. To tie a bow around things:

There will always be hyper-critical open-source projects in which vulnerabilities spell chaos for the global software ecosystem. This is unavoidable.

Companies can and must do better to recognize the true costs of these vulnerabilities, and should respond in at least two ways:

Helping projects decrease their blast radii by funding additional maintainers, governance, and practices that ensure continuity and response when the inevitable happens.

Helping maintainers decrease their blast radii by identifying critical projects with low bus factors and insubstantial support. And that doesn’t mean offering them server credits so that they can dogfood the company’s new CI product: it means paying them, in cash, for the work they provide.

Continuous integration access, GitHub organization management, release tokens, codesigning certificates, &c. ↩

i.e. popularity, adoption, whatever. ↩

Probably the overwhelming majority, if we consider a “project” to be something like a repository on GitHub. ↩

Limited public applicability being a large and reasonable one. ↩

Feel free to bury me on the day I become one. ↩

Measured in money and/or money equivalents, like engineer-hours. ↩

Maybe this should be higher? I don’t know; this is a first blush. ↩

There is, of course, a great deal of wiggle room with what “sustainably funded” means for any given open source project; it can be anywhere from $100 and free CI credits to a multi-million-dollar foundation budget and multiple in-person all-expenses-paid developers’ summits. This alone requires far more rigorous attention than we’ve given it. ↩

More endpoint security software! Pay for another SOC 2 vendor! Make every engineer pinky promise not to introduce vulnerabilities! ↩

I don’t know the exact number. ↩

curl https://formulae.brew.sh/api/analytics/install/30d.json | jq -r '.items | .[] | .count' | tr -d ',' | awk '{s+=$1} END {print s}' ↩

I suspect I’ll never know exactly how many. That being said: CapitalOne, Google, Stripe, Square, Slack, and a number of other very large companies appear to sponsor CocoaPods, strongly indicating that it (and thus, transitively, me) are part of their development ecosystem. ↩

Names have been removed not because it’s a secret or shameful, but because it doesn’t add anything to the story. They haven’t done a single thing wrong. ↩

Some good metrics being whether maintainers are de facto “on call” for companies they never agreed to work for, whether they are chained to their projects professionally, &c. ↩

We aren’t going to (and shouldn’t) get rid of libc, the Linux kernel, OpenSSL, &c, and memory safety alone won’t save us. ↩

Either my time or others. ↩

And don’t read this as an anti-IR or blue-team screed: those teams are vital! No amount maintainer compensation will perfectly eliminate vulnerabilities or the need for talented individuals on staff to perform response. ↩

It’s also not an oblique demand for payment. I am already paid to work on open source. I want others to be paid. ↩