Jan 22, 2018 Tags: programming, workflow

This post is at least a year old.

I often reference the manpages when giving a development

presentation or talk, but I’ve only recently come to realize how few people are both comfortable

with the man interface and adept at discovering information through it.

This post is my attempt to share some of the tricks and techniques I’ve picked up over years of reading manpages.

The manpages (short for “manual pages”) are the oldest and longest-running documentation collection on *nix, stemming back to the first edition of the Unix Programmer’s Manual in 1971.

On a modern system, the man command is the most common way to access the manpages:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

# access the first manpage named "time", which happens to be time(1)

man time

# access a specific section's "time", in this case the C time function

man 2 time

# attempt to access a nonexistent "time" in section 5

man 5 time

Because the manpages were originally published on paper, they were (and continue to be) typeset with

troff on most systems. Today, the man command (and other

manpage readers) invoke troff internally and pipe the output to the user’s

pager (like more or less).

In fact, a very simple manpage reader (which only works with section 1) can be implemented with just three commands pipelined together:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

function myman {

# `-t` and `-e`: run `tbl` and `eqn` on the input, for tables and equations

# `-mandoc`: use a set of troff macros specifically for manpages

# `-Tutf8`: output UTF-8 text rather than PostScript

gunzip < /usr/share/man/man1/"${1}.1.gz" | groff -t -e -mandoc -Tutf8 | less

}

myman gcc

myman ls

Apart from their simplicity and adherence to the UNIX philosophy, man and the manpages serve a

number of important roles:

They provide a categorization: section 1 is for system commands, 2 for system calls, 3 for library functions, and so forth. This categorization is followed both by the system itself (which populates several of the sections) and by programs installed by the user or package manager.

They provide offline documentation: man doesn’t require an internet connection, and can provide

much of the documentation that an internet search would yield.

They offer canonical information: searching for a command or function online might tell you

whether it exists, but won’t tell you the flags, arguments, or behavior specific to your system.

For example, man ls will tell you whether your system’s ls is BSD or GNU (and the differences

therebetween). The manpages (on Linux) will also tell you which feature macros you’ll need to define

in a C program in order to use a function (or a variant of a function).

So, let’s move on to some techniques.

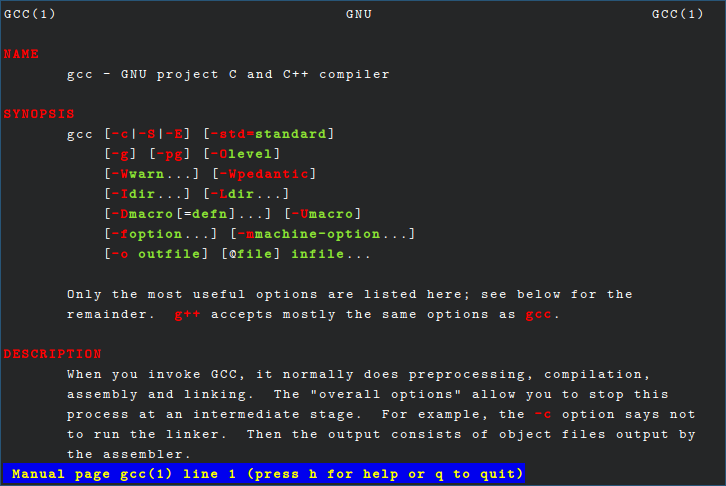

One of the simplest things you can do to enhance the readability of manpages within man is to

colorize the pager’s output:

In less, this is accomplished by setting the LESS_TERMCAP_* environment variables to your

preferred ANSI color codes. Here are the variables you can set:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

LESS_TERMCAP_mb # blinking mode (not common in manpages)

LESS_TERMCAP_md # double-bright mode (used for boldface)

LESS_TERMCAP_me # exit/reset all modes

LESS_TERMCAP_so # enter standout mode (used by the less statusbar and search results)

LESS_TERMCAP_se # exit standout mode

LESS_TERMCAP_us # enter underline mode (used for underlined text)

LESS_TERMCAP_ue # exit underline mode

You may be able to set others corresponding to the termcap capability names, but the variables above should cover all of your manpage needs.

By way of example, here is the bash function I use to colorize my manpages:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

man() {

env \

LESS_TERMCAP_mb="$(printf "\e[1;31m")" \

LESS_TERMCAP_md="$(printf "\e[1;31m")" \

LESS_TERMCAP_me="$(printf "\e[0m")" \

LESS_TERMCAP_se="$(printf "\e[0m")" \

LESS_TERMCAP_so="$(printf "\e[1;44;33m")" \

LESS_TERMCAP_ue="$(printf "\e[0m")" \

LESS_TERMCAP_us="$(printf "\e[1;32m")" \

man "${@}"

}

Note that you don’t need to use escape sequences as above — tput will work just fine.

I mentioned some of the big sections above: 1 for system commands, 2 for system calls, and so on.

90% of man lookups will be in those three, but there are a few lesser-known sections that can also

be useful:

man 4 - Special files and devices

On Linux, section 4 is used to document special files, usually representing some aspect of

the machine or its peripherals. For example, man 4 mem will tell you how to use the

/dev/mem, /dev/kmem, and /dev/port files to read from and write to the system’s main

memory.

man 5 - Configuration files and formats

You probably know the /etc/shadow file, but do you know how its format is specified?

man 5 shadow will tell you that. Similarly, man 5 deb describes the .deb package format,

and man 5 ppm lists the spec for PPM images.

man Np - POSIX pages

These pages come in handy for contrasting POSIX behavior with the system’s behavior.

Some examples:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

# compare the system ls (on Linux, GNU) to the POSIX ls behavior

man 1 ls

man 1p ls

# compare the read syscall to the POSIX read function

# note the categorization: POSIX read is a function, not a syscall!

man 2 read

man 3p read

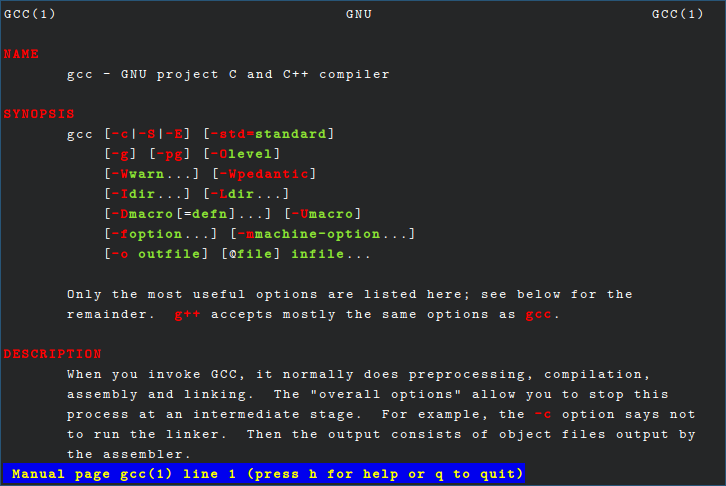

Like colorization, searching is more of a general less feature than one specific to man. That

being said, less’s searching and navigating features can make browsing the manpages a much faster

and more pleasant experience.

Searches in less can be forwards or backwards, using the / and ? commands respectively. The

search syntax is mostly POSIX ERE, but with some additions (man less has the details!).

For example, to find the first instance of “x86” in man gcc (watch the bottom of the screen for

the search prompt):

Observe that instances of the search term are highlighted with the standout colors from before.

Once a search term is entered, its results can be navigated via the n and N commands, which

move forwards and backwards in the results list respectively. For example, going through all

of the results for “Windows”:

When the last result has been jumped to, the statusbar changes to “Pattern not found”. Once that

happens, as in the video above, previous results can be returned to by hitting N.

Even this can be simplified: the & command can be used to display only lines that match the given

pattern. For example, retrieving every line that contains either “ARM” or “ABI”:

The effect is more dramatic when searching for the definition of a flag (in this case -D):

These commands are just the tip of the iceberg — less supports searching multiple files at

once, jumping around scopes (opening and closing parentheses, braces, brackets), and marking the

current location for later return. Each of these is documented on the help screen, which you can

get to in any less session via the h command:

Before picking up these tricks (especially searching), the manpages were an item of last resort

for me: I would search the internet or ask a friend, with mixed results. I had no real idea how to

use less, and would just clumsily page around until I found what I was looking for. More often

than not, I would give up entirely.

At the end of the day, the manpages (and the man interface) are not perfect — there’s no

hyperlinking or real cross-referencing, and the entire corpus is written in a 45+ year old

typesetting language designed for physical output, not display in a virtual terminal.

That being said, they’re a fantastic initial resource for pretty much anything concerning your system — they remain up-to-date (unlike blogs and articles), they’re accurate and concise, and they’re very UNIX-y (text files and pipelines!).

This post was discussed on HN; a response by ‘djeiasbsbo includes some additionally useful tricks and advice.