(The 2.3 failure was a simple type error.)

(The 2.3 failure was a simple type error.)Oct 26, 2017 Tags: devblog, programming, ruby

This post is at least a year old.

Update (5/16/18): Much of the information below is now obsolete, thanks to the new keybase oneshot

command. keybase help oneshot has all of the details, and you can find an example of it in use

here.

This is a post-mortem analysis of my work on getting the Keybase client running on Travis CI.

Hopefully it will help the half dozen other people running Keybase in a CI setting.

I maintain an open source secret manager, KBSecret, that uses Keybase and the Keybase filesystem (KBFS) for encryption and synchronization.

KBSecret is written in Ruby and interacts with Keybase through a collection of unofficial libraries I wrote.

It exposes both a public API (in Ruby, of course) and a well-featured CLI via the kbsecret

command. Both the API and CLI have unit tests to prevent regressions and provide a semi-rigorous

specification of the overall program.

Since KBSecret integrates tightly with Keybase and KBFS, its unit tests need to make several assumptions about the test host in order to do any meaningful testing:

/keybaseAs a developer testing on my own system, these are mostly reasonable assumptions to make. I can automate the suspension of my own (real) KBSecret state, and I certainly have Keybase and KBFS running.

However, I really like farming out the work of testing to a CI service — CIs make it impossible to forget to run your tests,1 and they give new contributors immediate and automated feedback on their changes. Auto-generated coverage reports are also nice, as they provide a metric for the project’s overall health.

My first approach to running the KBSecret tests on a CI was to abandon Keybase entirely, and attempt to stub a subset of Keybase functionality2. At a high level, the stubbing looked like this:

TEST_NO_KEYBASE in the environment, and…

Keybase.current_user with "dummy"require-ing any KBSecret or Keybase files that would throw exceptions on load

(testing for a keybase process or similar)I completed my first version of this on August 1, and you can see the changes here.

Thus, there were two ways to run the unit tests:

1

2

3

4

5

# run tests as normal, assuming a real Keybase installation

$ rake test

# run tests with Keybase stubs

$ TEST_NO_KEYBASE=1 rake test

Both of these were placed under the make test target, to prevent me from accidentally introducing

changes that broke one or the other while developing locally. Meanwhile, the .travis.yml file

only contained the second invocation.

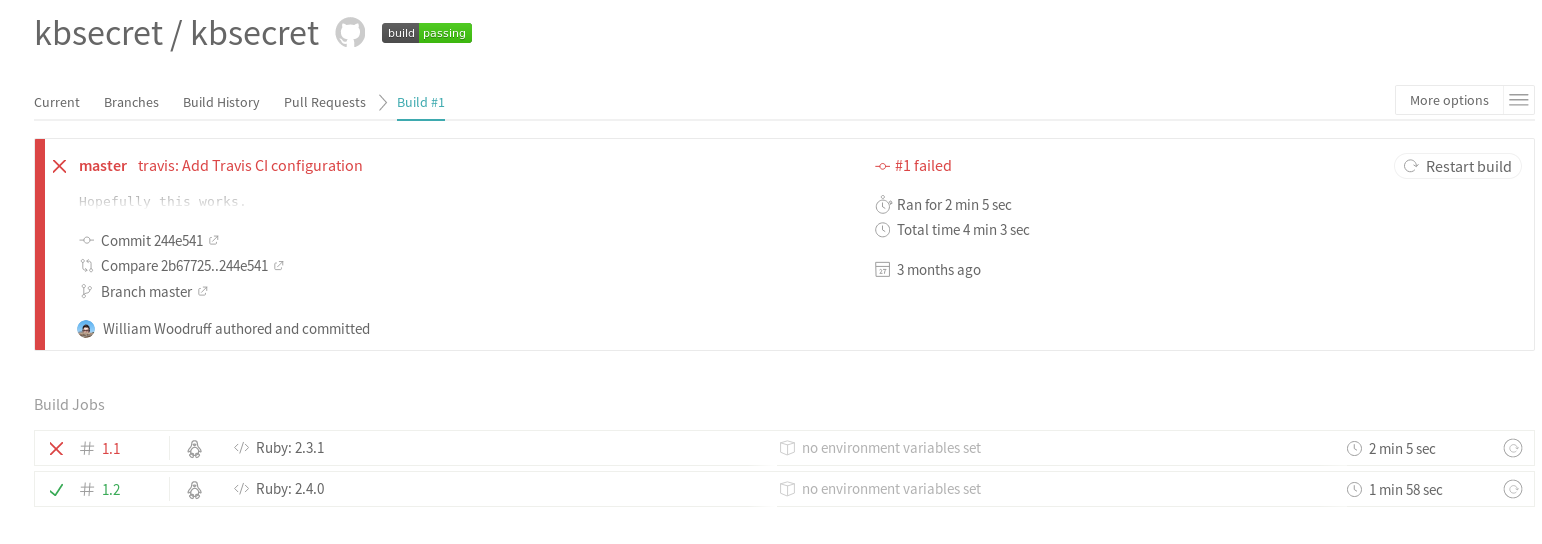

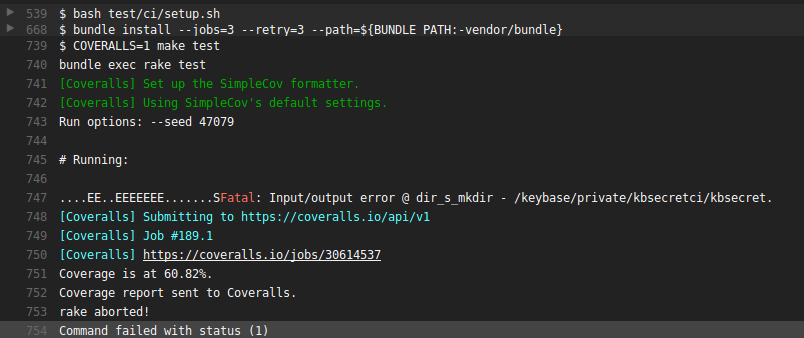

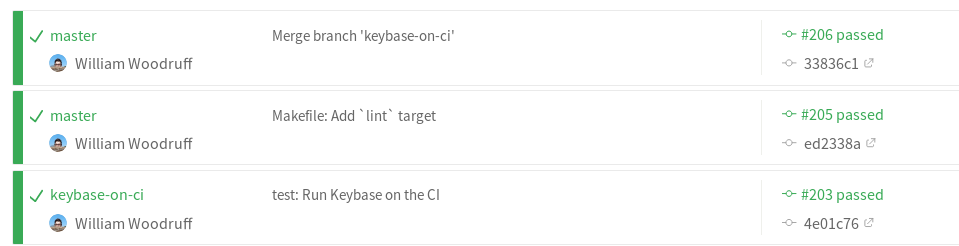

Voila:

(The 2.3 failure was a simple type error.)

(The 2.3 failure was a simple type error.)

The stubbing setup actually worked pretty well for a while, despite its hackiness. With the exception of a few changes caused by ongoing development, it required no maintenance or afterthought. It was also fast, with test and coverage results across two separate machines taking just over a minute on average to complete.

Everything was dandy…until I wanted to add the CLI tests to the CI. I quickly realized that

continuing with the stubbing approach would require considerable effort — I would have to

mock a great deal of Keybase and KBFS behavior (like user and team validation), and layer on

even more require muckery to avoid throwing exceptions due to the process barrier between

the keybase command and its subcommands. The result would be a half-functional Keybase mock

that still wouldn’t cover the corners needed to test the CLI satisfactorily.

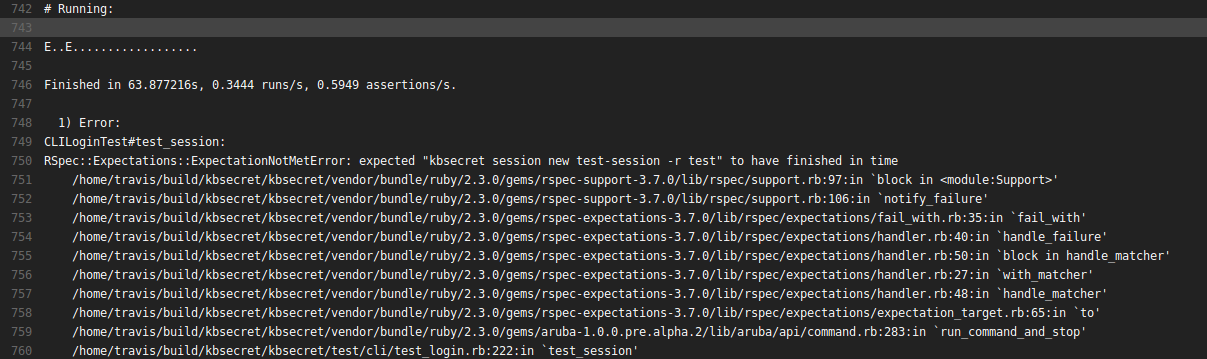

Given the problems with testing the CI above, I decided to throw my stubbing approach out entirely and try running the real Keybase client on the CI.

Can the Keybase client even run on a headless machine? Some quick searches confirmed that it could.

Installing the client turned out to be relatively easy:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

# download the .deb from Keybase's servers

$ curl -O https://prerelease.keybase.io/keybase_amd64.deb

# install it directly

$ sudo dpkg -i keybase_amd64.deb

# ...and then fix all the broken dependencies it expects

$ sudo apt-get install -f

run_keybase then starts the Keybase service and KBFS daemon correctly, and we’re left with

the task of automating the log-in process. This is where it gets tricky.

Keybase’s CLI is heavily interactive — most commands prompt the user for input, and assume that the user is on a TTY. ANSI colors and effects abound.

None of that is bad (it actually makes keybase very pleasant to use), but it poses a challenge

when trying to automate things like keybase login and keybase deprovision (more on those below).

I spent a lot of time fiddling with different ways to do interactive automation, but I ended up

going with good old expect and autoexpect for automatic

generation:

1

2

3

# `kbsecretci` is the name of the KBSecret CI account on Keybase

$ autoexpect -c -f setup.expect keybase login kbsecretci

$ autoexpect -c -f teardown.expect keybase deprovision

This ended up working way better than I any right to expect (no pun intended). You can see the

generated scripts (with some manual parameterization and fixups)

here and

here. Note

the KBSECRETCI_PASSWORD environment variable — that contains the account’s password,

and was configured directly in Travis.

Keybase keeps track of the list of “provisioned” devices associated with an account. When a new device (like, say, a new CI instance) sends a log-in request, an existing device must be used to (interactively!) confirm the validity of the request and provision the new device. This is great for security, but awful for automation.

There are two exceptions to these requirements: the first device on a Keybase account, and provisioning via a “paperkey” device.

The first device exception is what I tried first: by provisioning the CI instance as the device and them deprovisioning it once the tests ended, I could functionally avoid the device confirmation step indefinitely. In order to prevent multiple CI test jobs from competing to become the “first” device (and thereby clobbering each other), I also had to configure Travis to only run one job at once.

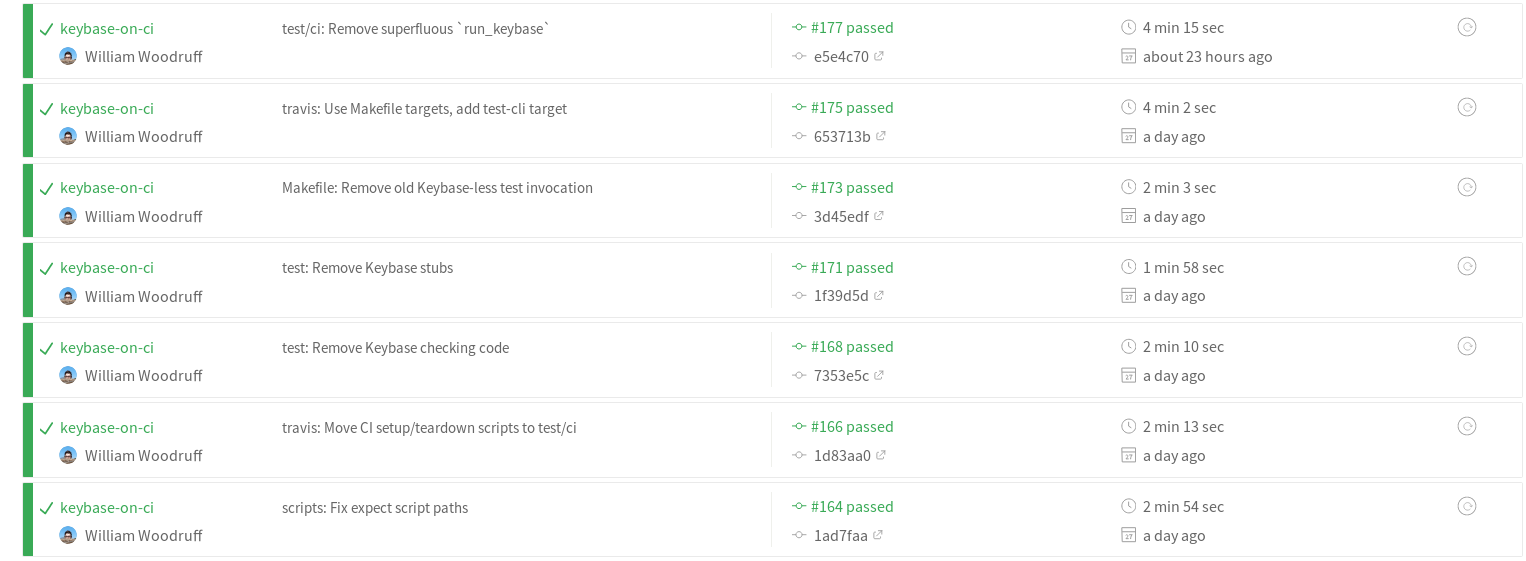

This worked really well for a while:

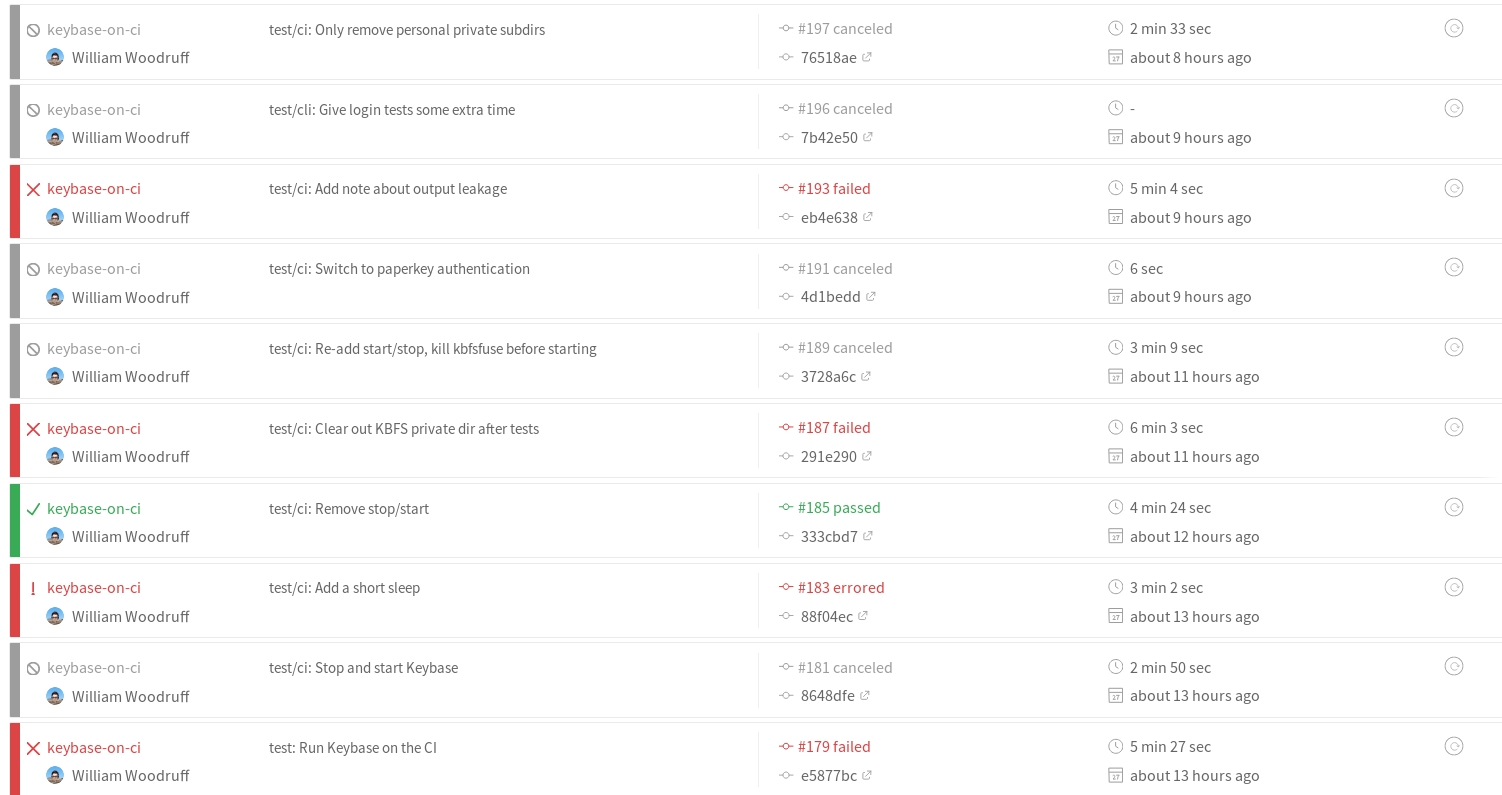

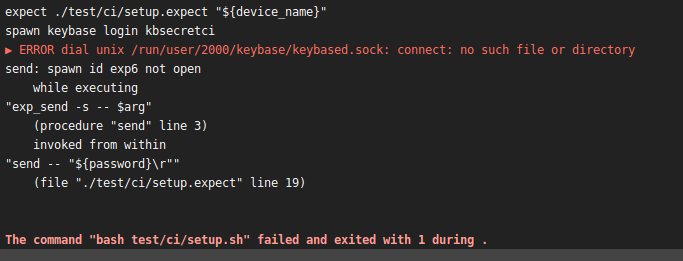

…and then broke fabulously:

I still don’t know fully why this approach started failing (I have some guesses involving PGP keys and some persistent bad state), but it did so in myriad ways:

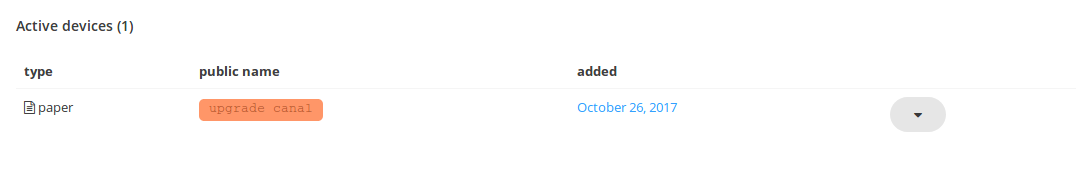

Since repeatedly provisioning and deprovisioning just one “first” device on the account wasn’t reliable, I switched to the other exception to the device confirmation rule: paperkeys.

Keybase paperkeys are a lot like normal cryptographic paperkeys, except that they’re human-readable (rather than just machine readable). They also function as devices, allowing a user to authenticate new devices by selecting their paperkey from the device list and typing it in. That means we can use one to provision our CI instances!

Just as with the passkey method, we’ll keep the CI limited to one job at a time and still

deprovision the device at the end of the run. This prevents the list of devices presented

during keybase login from growing indefinitely, which in turn keeps the expect script for

the paperkey method relatively simple:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

set device_name [lindex $argv 0]

set paperkey $::env(KBSECRETCI_PAPERKEY)

set timeout -1

set send_slow {1 .1}

spawn keybase login kbsecretci

match_max 100000

expect -exact "\r

The device you are currently using needs to be provisioned.\r

Which one of your existing devices would you like to use\r

to provision this new device?\r

\r

1. \[paper key\] upgrade canal\r

\r

Choose a device: "

sleep .1

send -s -- "1\r"

expect -exact "1\r\r

Please enter a paper key for your account: "

sleep .1

send -s -- "${paperkey}\r"

sleep .1

expect -exact "\r

\r

\r

\[35m************************************************************\r

\[39m\[35m* Name your new device! *\r

\[39m\[35m************************************************************\r

\[39m\r

\r

\r

Enter a public name for this device: "

sleep .1

send -s -- "${device_name}\r"

expect eof

We also (experientially) need to give keybase some time to start up, so the whole setup process

for Keybase on Travis looks something like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

set -ev

sudo apt-get -qq update

curl -O https://prerelease.keybase.io/keybase_amd64.deb

set +e

# this command will exit with 1, so don't let it take down the job with it

sudo dpkg -i keybase_amd64.deb

set -e

sudo apt-get install -f

sudo apt-get install expect

run_keybase

sleep 3

# the device name here is just the current timestamp, down to the milliseconds.

# this is sufficient, since the CI is configured to only run one process at a time,

# and devices are deprovisioned immediately after all tests complete.

device_name=$(date +%s%3N)

# NOTE: it's VERY IMPORTANT that no output from this command appear in public logs,

# since `keybase login` echoes the paperkey back to the terminal. If the paperkey gets leaked,

# anybody can fiddle with the CI account.

expect ./test/ci/setup.expect "${device_name}" > /dev/null 2>&1

sleep 3

(Note the redirection of expect’s output, since paperkeys get echoed by keybase login, unlike

passphrases.)

Hacky, but now we have real Keybase working reliably on a headless CI!

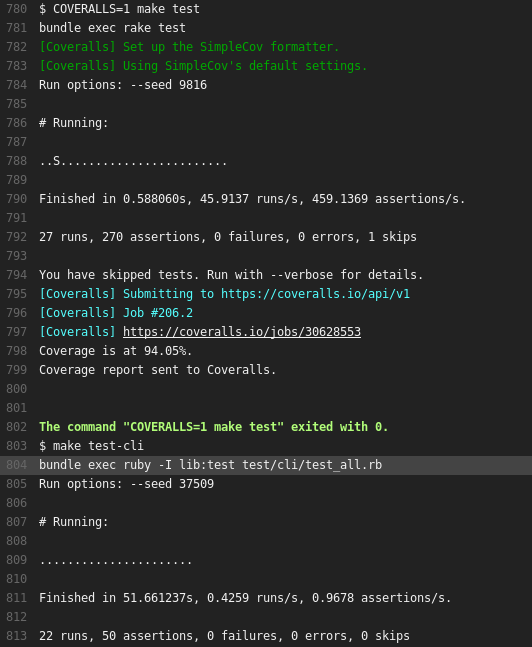

With both API and CLI tests:

This post was pretty scatterbrained, so I’ll just list everything you need to replicate my setup down here:

KBSECRETCI_PAPERKEY (or whatever you rename it to) in Travis’s environment

configuration (or some other secure location), to avoid leaking it to the worldThanks for reading!

- William